by Katie Worthington Decker

When Thibault Manekin was a young boy, he had a life altering experience that came in the form of watching the movie Mississippi Burning. He describes the scene of the church massacre when a KKK member assaults a young boy around the same age as him, just 10 years old. Distraught, he comes to ask himself two important questions, ones many of us as adults probably still ask ourselves in today’s reality;

“Why are we as a people so divided” and “What can I do to creatively help bridge the divide”.

It’s because of this moment and those questions, Thibault describes, that the trajectory of his life changed forever.

Bridging the Divide

At our February meeting, LEDC investors, Catapult entrepreneurs, community advocates, and civic and government leaders heard from author and social entrepreneur Thibault Manekin. He discussed his life’s journey, one that has focused on making a difference through “reimagining industries, leading with purpose and growing ideas into movements.”

This was one of those meetings where you sit there thinking, “There should be a stadium full of people hearing this message.” Inspiring – yeah, that’s not even a meaningful enough word to describe it.

So, how did he end up in Lakeland? Well, that’s a fun story. You may not be aware, but Catapult has caught the eye of entrepreneurs across the nation. Two of those entrepreneurs that visited Catapult were accepted into an elite start-up bootcamp in Baltimore and as they became familiar with the ecosystem there, they encouraged our LEDC president Steve Scruggs to visit. For those of you who know Steve, a visit to a city is a fact-finding mission to gather ideas and best practices to bring home for the betterment of Lakeland.

As he heard about the you’ve-got-to-meet changemakers in Baltimore, he was connected with Thibault Manekin. They had a conversation; one Thibault described to the audience as Steve having genuine curiosity to see into his soul – to understand his purpose. It was a discussion so impactful that he decided he had to visit Lakeland.

So, who is he, what does he do, and, more importantly, WHY does he do it?

Thibault shared that as he grew up from the young boy irrevocably imprinted from watching that powerful movie, he found more and more reasons to continually ask himself those two important questions; “Why are we as a people so divided” and “What can I do to creatively help bridge the divide”.

When he graduated college, he realized that he had a choice. He could either, “sit on the sidelines and hope that someone else can do the heavy lifting, or, he could be the one that does the heavy lifting.”

So he joined his friend Sean from college, someone totally aligned on living life with purpose, who had started a company with his brother called PeacePlayers. This international non-profit launched off of an idea that they would go to deeply divided, war-torn countries and use sports, specifically basketball, to bridge the divides, develop leaders and help change perceptions.

So with $8,000 in funding (which he points out to the Catapulters in the room, felt like they had raised $1M), they fly to South Africa. There were a lot of people there, all white people, he notes, lecturing them with fear-filled warnings on how to approach their mission. Don’t do this, don’t do that. It’s too dangerous.

So, what do they do? Ignore the fear and do it anyway. For Thibault, it began in a rural field, 100 Zulu children and a soccer game. The interaction, starting with trepidation and palpable tension, became one of trust and friendship through sport. Emboldened, they begin the program in numerous locations and schools in South Africa.

It caught the attention of Nelson Mandela, who famously said, “Sport has the power to change the world. It has the power to inspire. It has the power to unite people in a way that little else does.” Nelson Mandela’s foundation made a sizeable investment which helped the non-profit to grow. PeacePlayers still exists today and has spread from its beginnings in South Africa and Northern Ireland to the Middle East, Cyprus and, in 2017, to the US to “address pressing social divides” in several cities.

From this phase of his life, he shared with the audience that he learned an important lesson:

There will always be a million people telling you why you CAN’T do something. Telling you NO. Use every “No” as your motivator. Use every “No” as your teacher. Use every “No” as your catalyst to deepen listening and curiosity.

What is your purpose, your why?

As he grew weary of international travel and got the nagging urge to settle, he returned home to Baltimore in 2006. He was at that phase of his life many of us experience, the uncertainty of what’s next.

He began think:

- What is your purpose, your why? What burning questions are keeping you up at night?

- What is the one thing you could do for work every day for the rest of your life?

- How can you reimagine what you love the most around the purpose that drives you?

As he examined his own hometown of Baltimore, he came to realize two things:

- Our country, and in particular his city of Baltimore, was more divided than many of the war-torn countries he had visited. He attributed this to Americans inability to have an open and honest conversations about our similarities and, more importantly, our differences, with people who don’t look and think like us.

- The real estate industry, i.e. the control and ownership of land, was the most powerful and connected industry on the planet. It touches everyone one of us – the buildings we work in, the schools we send our kids to, the parks we play in, etc. Everything has been carefully planned for us without us knowing it. And even though it has an incredible power to connect us, the industry itself, historically, has done more to divide us than to bring us together.

With his father, Donald, he decided he wanted to start a real estate company focused on helping to bring people together to affect actual change. They asked themselves:

- What if real estate was used to empower communities?

- What if real estate happened with communities not to them?

Out of this purpose they founded a company called Seawall. Like many entrepreneurs, they had no idea what it would look or feel like, but they knew they needed to take a first step.

What they did know was they wanted to re-imagine the real estate development industry so that the built environment empowers communities, unites our cities, and helps launch powerful ideas.

The first challenge they decided to tackle, marrying his dad’s experience in both real estate and public education, was the challenge Baltimore was having with recruiting and retaining teachers. They thought:

- How can real estate not just attract brilliant young teachers to Baltimore, but actually help retain them?

- How might they create a place that offers affordable housing to teachers taking the leap into teaching in the challenging urban core?

- How might they create shared space that creates an outlet for teachers to find support with each other, in their common experience, aspirations, frustrations and challenges?

- How might they create an environment that empowers these teachers and provides access to non-profit organizations working to support education?

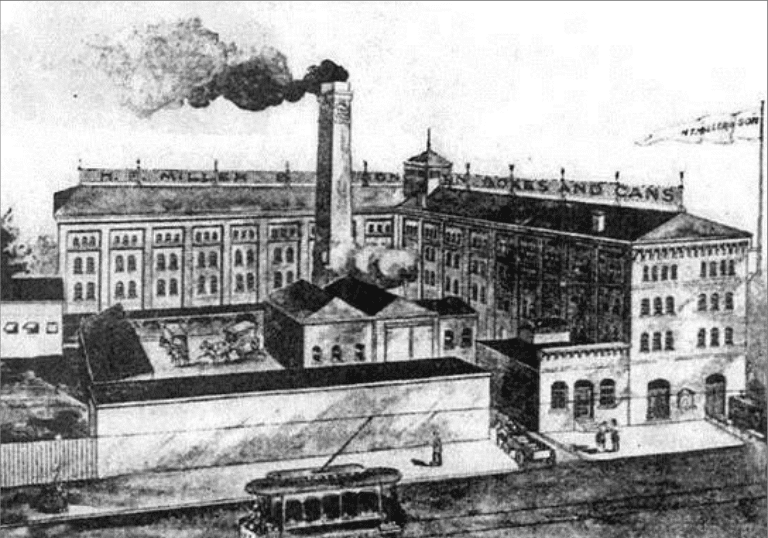

Through the power of real estate, they set out to create the Center for Educational Excellence at Miller’s Court. After months of searching, they found a 100,000 sq. ft. abandoned factory in complete disrepair after 30 years unoccupied in the neighborhood of Remington. They believed it to be the perfect space, and through the noise of “no’s” and “you’re crazy”, they pushed through by focusing on three groups:

- End users

- Community

- Team

Shared Ownership

What the Manekins recognized early on was to make this idea work, you had to create a movement around it. You had to transfer ownership of the idea.

One of the most powerful takeaways from Thibault’s dialogue at this meeting was the notion that the more you claim an idea as your own the more you stunt its growth. By opening the idea up to become a movement, you give it oxygen and then anything is possible.

It was the three groups of stakeholders they engaged that made this dream a reality:

The End User: To breathe life into the idea, they first started with the end users – teachers and non-profits. These groups were taken on tours and unlike many other business-types, they saw a building with opportunity and promise. They became a part of the design team and were linked directly to the architects and engineers to create the plans for the space. They also helped to inform the business plan – what did affordable housing mean to them? What could they afford in rent?

The Community: The community of Remington was fiercely protective of their neighborhood. They had discouraged numerous other developers through pressure from their neighborhood association. Thibault and his father requested a community meeting and pitched them their idea of the Center. He conveyed that they wanted to come in as neighbors, not guests. They asked if the neighbors wanted to be involved in helping bring the project to fruition. The community was on board, but they had a request. They thought the idea was great, but they wanted something that would allow their community to participate in the success of the tenants in the building. They wanted a place for the community to engage with each other, they wanted. . . a coffee shop. Done. The community took ownership of the project and even protected the building during construction.

The Team: Who are the people in life that have certainly succeeded, but have also failed more than you have succeeded? Meaning who can help you navigate obstacles through lessons learned through their failures. Who could be the projects guardian angels? One of the biggest hurdles was in fundraising. Discounted rents combined with $20 million in construction was not a formula that would work out out on any spreadsheet. They reached out to contacts that had experience in real estate lending and these angels of Bart and Joe were able to introduce them to tools like the New Market Tax Credits, a federal program designed to help spur commercial development in low-income communities, as well as Historic Tax Credits. Having the support of the experienced lent credibility to the project which led to more investment including low-interest loans from the State and City.

The project was fully rented before they were even done with construction and continues to have a waitlist each year. It has been replicated in numerous locations. Seawall has gone on to build additional community gathering places, teacher housing to create opportunities for ownership, state-of-the-art schools, advocated for rezoning and redevelopment of areas to house new small businesses and more.

When asked about gentrification concerns, Thibault got real. He said that this was an area they failed in the beginning. They should have understood their impact more. They should have purchased and encouraged others to purchase more real estate to protect it for the community. They should have set expectations for the community on what could happen. They are doing these things now with new projects, but as he reflects, he admits they did it late for the Millers Court project.

Thibault was asked what was next for him. He’s bridged division through sports. He’s bridge division through real estate. What now?

Interestingly, he pitched the question back to the audience.

How can you reimagine your industry to positively affect change in your community?

As the LEDC begins to launch the Catalyst 2.0 effort to plan for downtown Lakeland, we want to ensure that we are living by the principles Thibault shared. We want the community to take ownership over the future of Lakeland. We look forward to continuing the conversation of how real estate can empower communities.

View photos from the meeting below: